By Betty Hoover DiRisio (LCHS Board Member & Volunteer)

After the U.S. entered World War I, Black selectees from the Pittsburgh area, nearly all educated, many of them having college training, found themselves being assigned to service battalions as stevedores. These men participated in a sustained protest on the part of Blacks of Pittsburgh and vicinity.

WASHINGTON LOBBIED ABOUT INEQUALITY

In October 1917 a group of nine Pittsburgh area Black men stationed at Fort Lee, Virginia, secretly wrote about the Army’s restrictive policies. The conditions these soldiers encountered were described and sent home to influential Black leaders. These Black leaders lobbied Washington about the inequality and lack of opportunities for Black soldiers.

The protest was successful. As part of a military experiment, 16 men were transferred to an artillery organization at Camp Meade, mostly from the Pittsburgh area. All 16 soon became non-commissioned officers. The War Department was petitioned for a special order to permit the organization of a segregated Negro Artillery Regiment. The request was granted and a lieutenant and three sergeants were sent to Pittsburgh to induct Blacks recruits for the regiment.

MEMBER OF THE 351st FIELD ARTILLERY

The Pittsburgh unit, the 351st Field Artillery, left Camp Meade June 19, 1918 sailing from Hoboken, New Jersey and arriving at Brest, France June 26th.

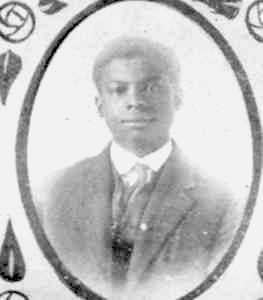

Among the 351st Field Artillery was George C. Stanton of 427 Taylor St., New Castle. George graduated from New Castle High in 1916, a member of the Adelphic Literary Society and Debating Team with dreams of attending Lincoln University. He was employed at the time of entry by the Pennsylvania Railroad in Sharon.

In August 1918, George wrote home telling of his life in the war, an example that “colored” troops could successfully handle artillery:

“This is the first-time colored men of the United States have ever attempted artillery, because it was formerly the general belief that they did not have the mechanical knowledge necessary to compete with the tasks which they would have to master. Perhaps that was so, but since then we have so far advanced that there is absolutely no reason under the sun that any thing anyone else can do should be impossible for us… There are men in this regiment from all walks of life. From waiters and day laborers up to men of the highest professions Doctors, lawyers, professors of art, literature and languages. There are few men who do not have at least a passable education and absolutely none who are illiterate. This is a picked regiment of carefully chosen men as far as possible every possible precaution to safe guard health is taken.”

PERFORMANCE WAS EXCELLENT DESPITE LITTLE ACTUAL ARTILLERY TRAINING

The unit was part of the 167th Brigade and was initially given little actual artillery training. A month after arriving in France, the 351st Field Artillery still had not fired its 155mm French howitzers. When the brigade moved into sector, it was finally equipped with tractors and motor vehicles to make it a completely motorized unit. It capably supported the 92nd Division’s attacks during the final days of the war. Brigadier General (Brig. Gen) Malvern Hill Barnum, a career cavalryman, reported that the divisional artillery supported the infantry advances and its performance was excellent.

The Black artillerymen also received congratulations from General John J. Pershing, who told them, “You men acted like veterans, never failing to reach your objective, once orders had been given you. I wish to thank you for your work.”

STANTON RETURNS HOME

George came back to the U.S. with this historic unit in February 1919.

Arriving in Pittsburgh the unit received a great welcome and parade.

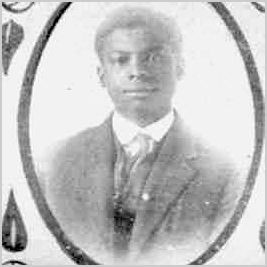

George Chancey Stanton

NeCaHi 1916

George Chancey Stanton, born January 22, 1897, was the son of Chancy and Josephine (Mosett) Stanton. By 1934 he had moved to the Philadelphia area. He became a funeral home director (mortician), civic leader, chairman of his church’s board of trustees and a long-time member of the NAACP. He married Daisy Griffin.

He died September 8, 1963 and is buried in Mt. Lawn Cemetery, Delaware Co., Pennsylvania.

Photo credits

- Part of Squadron “A” 351st Field Artillery

- Troops on the Transport Louisville returning home 1919

- NeCaHi 1916