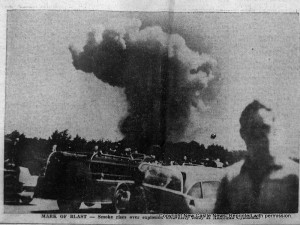

On July 6, 1964 there was an explosion at the American Cyanamid Chemical Plant in Edinburg, Pennsylvania. Five men were killed and many were injured.

Provided courtesy of Jeff Bales

Provided courtesy of Jeff Bales

The following is Chester J. Hoover’s oral history of the Power Plant and his eyewitness account of the day of the blast.

A Brief Oral History of the Powder Plant

I was 24, had a steady girl and working at the Powder Plant in the dynamite shed. My dad was employed at the plant, too. He worked in the Gel House. The dynamite shed was down the hill from the Mix house where nitroglycerin was mixed and fed down a hill in two tubes, one on each side of the mix house with a hill separating the two lines. Across from the dynamite shed on the other side of the hill was the Gel House.

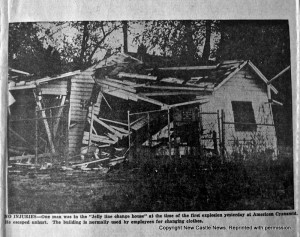

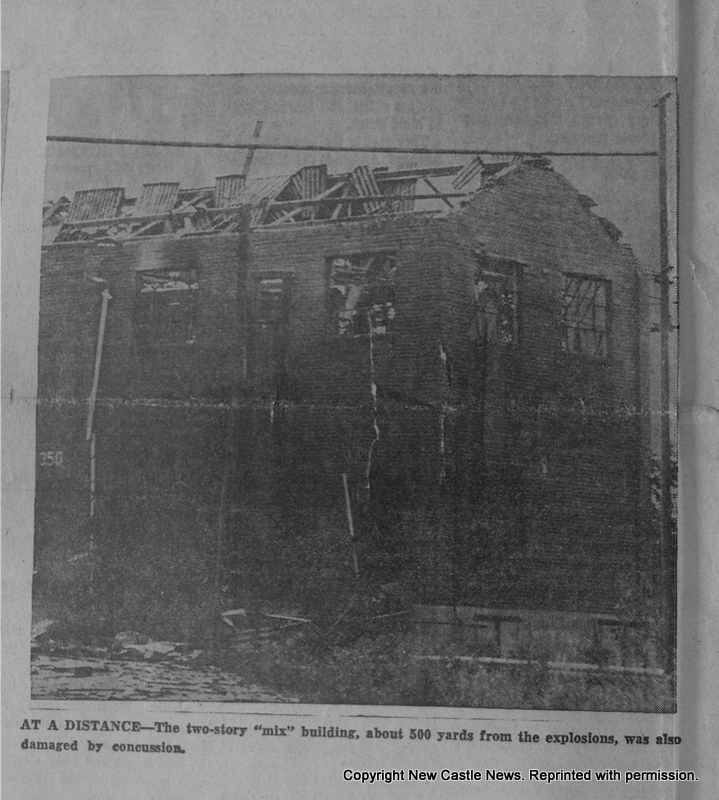

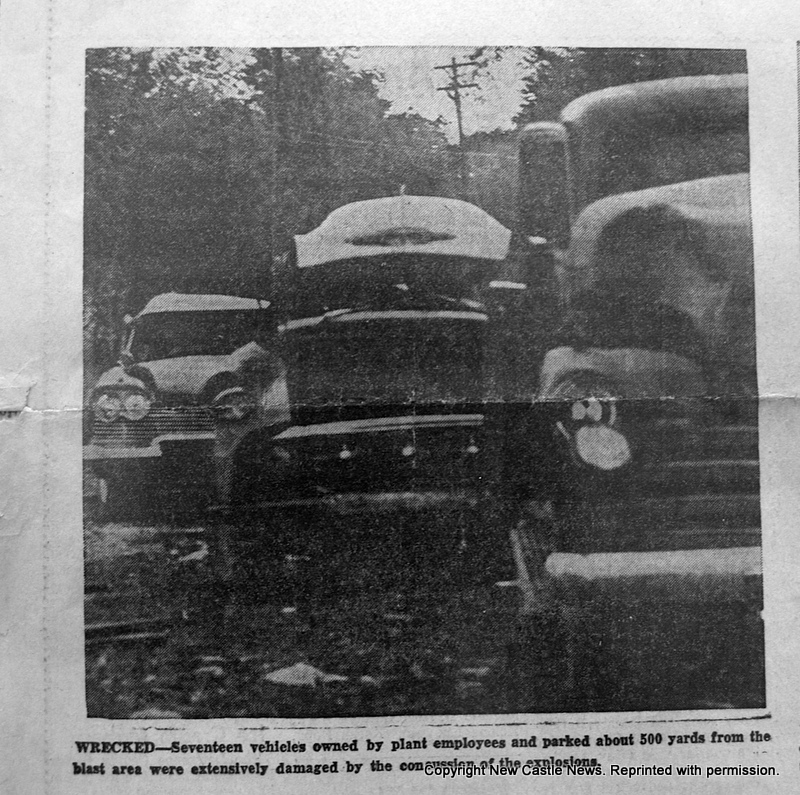

The houses or buildings were built into the side of hills or mounds in an S formation (one in each curve of the S). This was done so that if one house were to explode the percussion would not cause any of the other houses to blow and would hopefully avert a chain reaction. Buildings were built so that if there were an explosion the walls would blow out and the roof would fall in, in an effort to contain the concussion.

On the first day I came to work one of the veterans took me in the Mix house. There was a huge wheel where powder was mixed with liquid nitroglycerin forming a wallpaper-like paste. It would swirl around and around and then the paste would be gravity-fed through two lines, down the hill into a pack house. The paste had to maintain a constant temperature to remain stable. It was an operation that could not be halted once started. The old veteran explained to me that my job was to watch the wheel for sparks, so I earnestly began watching. He followed up those instructions with “as soon as you see a spark put your head between your knees and kiss you’re a** goodbye”. A humorous way to impart a serious message as to how dangerous my new work environment was.

Word had it that explosions weren’t the only danger to the employees. During my employment, there were men in their 40’s and 50’s who died from heart attacks. Other workers would say it was because they would drink, and nitro and alcohol was a deadly mixture. I became a teetotaler.

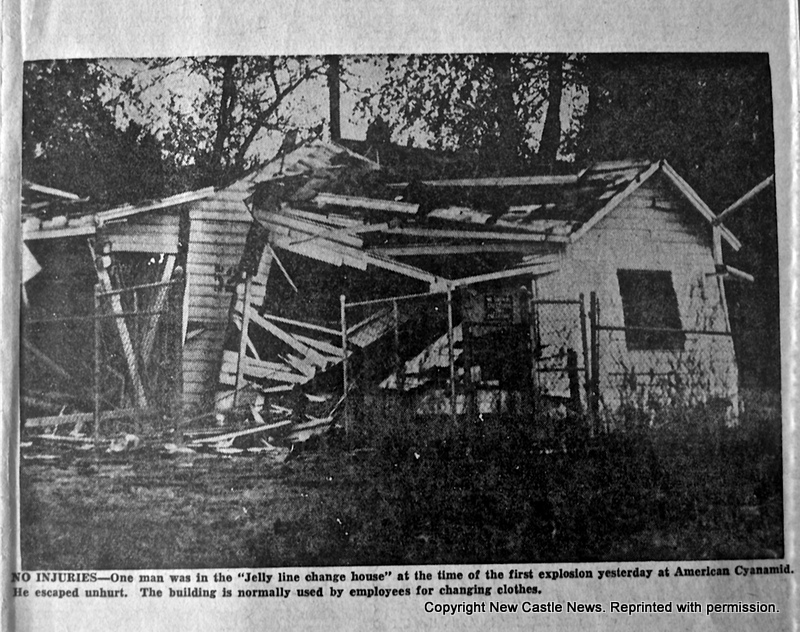

It was a deadly serious business and the company was big on safety. When we would arrive at work we would go into a “dress house”, and dress out in white pants, shirts and hats. All items of metal, like our car keys, were left in the dress house. Nothing of metal was allowed at the work site to avoid any possibility of a spark that could ignite the dust. When the day was done we would return to the dress house, remove the white uniforms, and shower, removing all of the explosive powder-dust from our bodies.

A Couple of Weeks Before the Explosion

A couple weeks previous, I had a dream that the plant exploded. I was telling the guys at work about it. In my dream I was in the dynamite house when I felt an explosion. I ran out the door, down over the hill and across the railroad tracks. I told them all, I kissed the ground, thanking the Lord for allowing me to make it out alive. My coworkers laughed, telling me that I had to get out of the “powder”, that it was affecting my mind. We all laughed.

The Explosion: July 6, 1964

I was working on dynamite line at the time of the explosion. My foreman was Jim “Oh Say” Hoover who lived in Edinburg. That afternoon I was writing mathematical calculations on the wall, figuring out how many payments I could make on my new GTO.

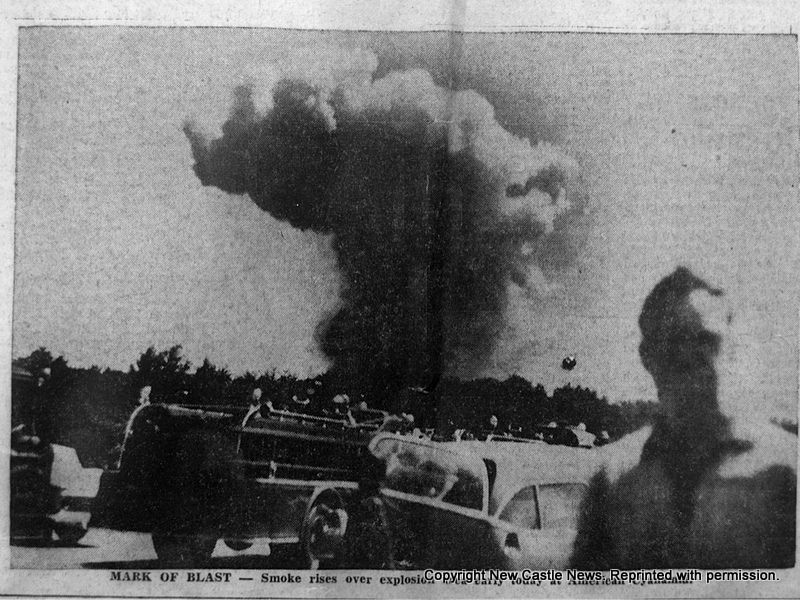

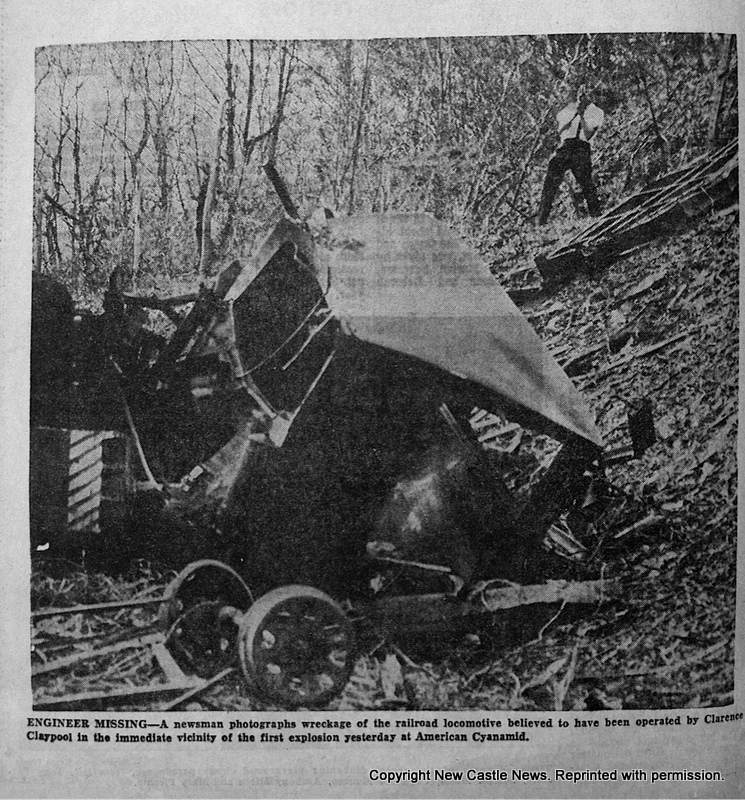

All of a sudden, things went into slow motion. I felt the floor rise up, the roof sway down and the guys in the dynamite shed were being blown sideways. Just as in my dream, I ran out the door toward the Gel House, but the difference was that in reality, a large man with a huge hand grabbed me by the back of the neck and turned me around, telling me I was heading toward the explosion, not away. Taking his instruction, I ran out the opposite direction, down over a hill and across the railroad tracks. There were three blasts within minutes of each other and then a fourth a short time later. It was utter chaos. Railroad tracks were twisted like pretzels. Enormous trees were ripped from the ground with their roots intact, and throw hundreds of feet. Soon sirens were heard from all over the area. Ambulances were arriving.

It was the Gel House (Building 362) that blew. My Dad! I searched around to try and find him when I saw one of the first ambulances pulling away. I peered inside and saw my father lying motionless and covered in blood. Not knowing if he was dead or alive, the shock hit me. I tried to find someone who knew how my Dad was. No one had any information. Authorities wouldn’t let me back up to get my car. Only emergency vehicles were allowed in. I was frantic. There was a fire truck coming into the compound. Pretending I was part of the security force, I hopped onto the side and directed them up the hill. I managed to get by security and made it to my car. About 800 yards away was a farmhouse. I stopped and asked to use the phone to telephone my girlfriend to let her know I was alive. There I was, in the farmhouse, on the phone telling her I was out safe (or so I thought) when another explosion went off. It blew out all of the windows in the farmhouse. By this time, most of the routes in and out of the area were blocked off. They needed to keep the roads clear for emergency vehicles.

As I was making my way to the hospital, I was shaking so badly I pulled into the old Airport Inn and downed a shot. (No tee-totaling that day!) I got back into my new car and back out on Rt. 224 heading down to Jameson Hospital. My Dad was one of the lucky ones, his ear was nearly cut off, he had head injuries, and hearing loss, but he was alive!

Dad was a “packer” in the Gel House

He cut the paste and pushed it down into a cylinder. The paste would come out the bottom of the cylinder through a horn or nozzle. Another worker would clamp on an empty tube and when the tube was filled, the caser put it into a crimping device to close the tube. Workers would be responsible to touch the horn periodically to make sure that the horn did not become overheated. Finished tubes would be stacked into cars and picked up by a dinky rail car and taken down the hill.

This day (July 6, 1964), the dinky car had just picked up a full car of nitroglycerin paste at the Gel House and had gone down the hill to prepare it for shipment. Had the blast occurred a few minutes earlier, the blast would have been unimaginable. Dad explained how the walls blew out and the roof collapsed on top of him. He managed to crawl out from under the roof and fall down over the hill before the larger blast that immediately followed that killed his coworkers.

After the first couple of explosions, a fire erupted around the mix house. There were still people inside engaged in the continued operation of it. [William J Wallace of Edinburg was one of the men who remained at his job after the first blast and was credited with preventing 10,000 pounds of TNT from exploding. Plant officials were afraid that the fire would affect the temperature of the mix and it too would blow.

The decision to evacuate 5 square miles of Union township was made. It was later learned that it was only a 5-lb. bucket of nitro that caused the shock wave that blew out the farmer’s windows. In the end five men were dead and four buildings destroyed. Officials concluded that the blast started in the Gel House most likely the result of the horn getting too warm and igniting the paste.

“I never did go back”

As soon as they let me in to see Dad, he asked me never to go back. The next day the company called the workers back to work to help search the grounds for human remains. I couldn’t bring myself to go. One of my coworkers called me that night and told me his story of finding one of the deceased worker’s boots containing his foot and another worker’s rib cage. Workers were so sickened from the sights, knowing these were the remains of their friends. “Be glad you didn’t go” was his statement to me. Honoring my Dad’s request, I never did go back. It wasn’t quite so easy for Dad. He was 50 years old and with his injuries, was not quite as marketable. He worked for a few more years there, but he was never the same. His health deteriorated and he died seven years later.

– Oral History provided by Chester J. Hoover

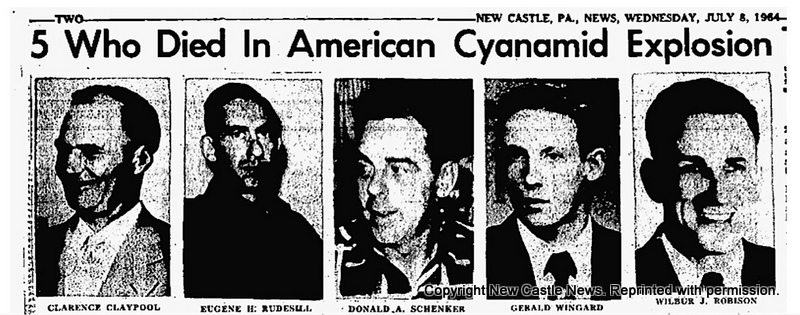

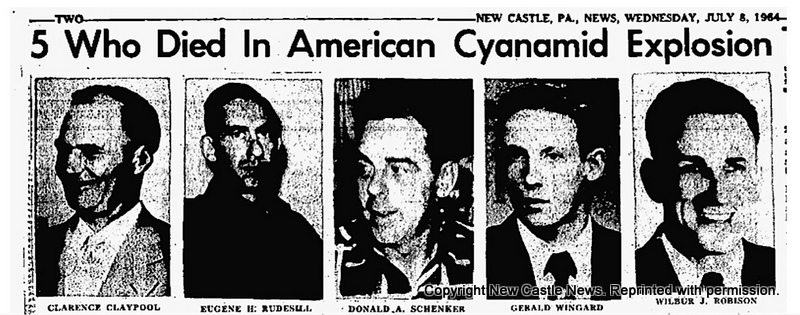

The Men Who Died in the July 6, 1964 Explosion

- Clarence Claypool, age 52, Locomotive engineer

Arlington Ave, New Castle PA. He was operating a train that was found 150 yards from where the first blast originated. - Eugene H. Rudesill, age 45, Gelatin Packer

- RD 7, New Castle PA

- Donald A. Schenker, age 37, Gelatin Shoveler

Pulaski PA - Gerald (Jerry) Wingard, age 29, Gelatin Packer

Mt Jackson Road, New Castle PA - Wilbur J. Robison, age 49, Caser

Union Township, New Castle PA

Injured

The following men were injured during the blast and treated at Jameson Hospital, New Castle. They worked in the Gel Stuffer Building (Building 362) with the exception of Smith. Smith was a dingy operator who was outside the building, but was hit by flying debris.

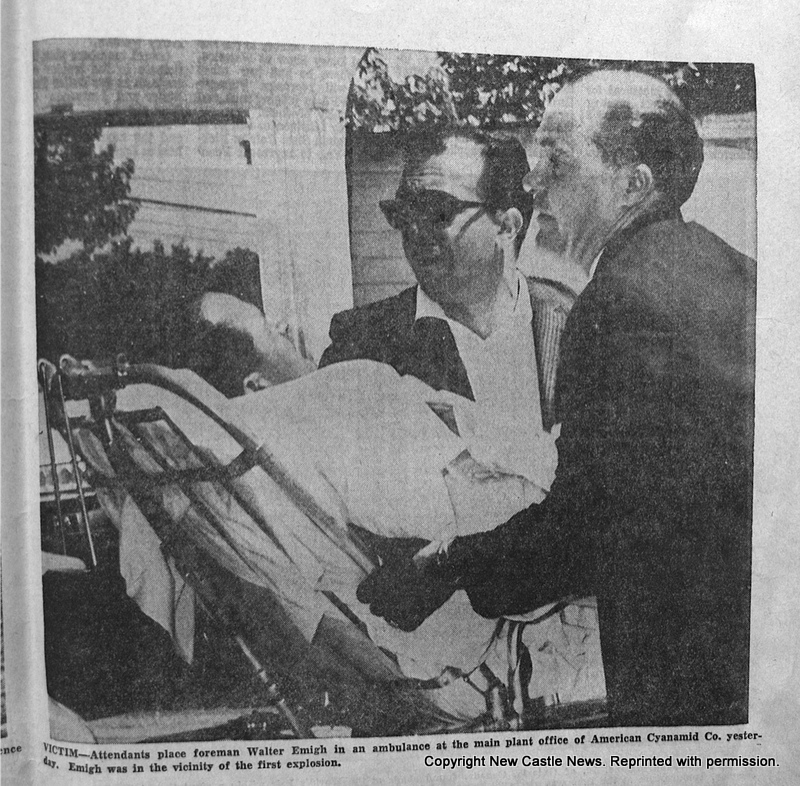

- Walter Emigh (foreman), Wilmington Ave, New Castle PA

- Harold Flowers, E. Wallace Ave, New Castle PA

- Harold Harry, E. Washington St, New Castle PA

- Chester Hoover, Mulberry St, New Castle PA

- Harry Smith, Edinburg PA

- Loyal Smith, Beaver St, Ellwood City PA

- James Snyder, Boyles Ave, New Castle PA

- Ronald Stetler, West Pittsburgh PA

Reprinted with permission

Earlier version posted on LCHS Facebook page on July 7, 2012

BOOK available in our Gift Shop and online: Dynamite! A Blaster’s History by J. Nelson McConahy

Link to news coverage of LCHS April 26, 2014 event commemorating 50th Anniversary of Plant Explosion