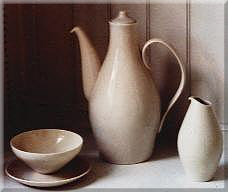

The Lawrence County Historical Society has the largest collection of Shenango China in the world. The men who started the first potteries in New Castle did so, not because of any clay deposits in the area, but rather because of the soft coal available which was used to fire the beehive Rims of that time. More than 500 of our 3,000-plus pieces are on display in our museum.

Shenango China Collection at the Lawrence County Historical Society

Our extensive Shenango China Archival Collection is one of the largest in the world. Please visit our museum and admire the beauty and fine craftsmanship of Shenango chinaware or explore the massive collection. Our archive includes the following rarities:

- Chinaware

- Decorating Books

- Correspondence

- Marketing Material

- Laboratory Data

- Photos & Slides

- Artwork

Introduction

It is Tuesday, March 24, 1992, and I’m standing with a crowd of people all clutching catalogs and white pieces of cardboard with numbers. Ahead of the throng is an auctioneer. We are at the sale of Shenango China, the equipment, buildings, and grounds.

As we walked through the plant, it was impossible not to feel the presence of the men and women who had worked in the plant during its 90-year history. You pictured the lines of print hanging in the Print Shop waiting for a fine craftsperson to place it on the ware as it began its journey.

Walking by the kilns, through the Decorating Department, Gold Room, Design Department, everywhere were ghosts, and the sounds of working people making something not only beautiful but useful. It was a product that touched the lives of heads of states and ordinary people. A point of pride.

With this exhibit, we explore the many facets of Shenango China from its earliest stages to its final days “A Lasting Legacy” of beauty, artistry, and craftsmanship.

– Beverly Zona, Museum Curator (1992)

Early History

In 1901, the New Castle China Company was organized. That year, they purchased the plant of the New Castle Shovel Works, a brick structure 275 ft. long and 80 ft. wide and a handle factory 87 ft. long and 32 ft. wide. To the shovel works, they added an extension 40 by 80 ft. This was the nucleus of the China Company. New buildings were added and kilns. They manufactured vitreous hotel ware and dinnerware for private homes. These operations continued for about four years. In 1901 Shenango China Company was also incorporated and a plant was built on the north side of Emery street. They made semi-vitreous hotel ware and dinnerware. They employed approximately 150 people.

In 1905, Shenango China experienced financial difficulty and a receiver was appointed. A new organization was effected and a charter was taken out under the name of Shenango Pottery Company. Again, difficulties arose. In 1909 and entirely new group took over the property headed by James N. Smith. Mr. Smith was a novice in the pottery business, he was part owner of the Smith-Kirk-Hutton hardware store. Under his direction, the company began to be established. James M. Smith has always been considered the founder of the company.

Shenango China purchased the plant of the New Castle Pottery Company in 1912, and the equipment was moved to the new facility. In March of 1913, the new plant was ready to open. Then came the flood of 1913, covering the plant to a depth of three feet. The opening was delayed until May of that year. They remained in continuous operation until December 1991. Mr. Smith was a man determined to succeed, if a machine did not do what he wanted, he built his own. One of his innovations was having raw feldspar shipped directly to the plant and ground there.

The men who started the first potteries in New Castle did so, not because of any clay deposits in the area, but rather because of the soft coal available which was used to fire the beehive Rims of that time. New Castle was at the center of the soft coal industry used in the making of steel. There was also money available for investment. Men in the steel industry had already seen the thriving pottery industry of East Liverpool, Ohio. With the beginning of World War I, the Company experienced sound and steady expansion. They built periodic kilns, ten bisque, ten glost, and one refractory. They also hired their first ceramic engineer at this time.

From 1909 until 1935, the entire production of Shenango Pottery was devoted to commercial china (hotels, restaurants, and institutions). In 1928 they built the first tunnel kiln and began to fire hotel china for the first time in this country. They also ran porcelain trials researching a vitrified fine china dinnerware product. They abandoned this idea only because of the Depression of the 1930’s. More tunnel kilns were built at this time replacing the beehive kilns. 1929 brought the first labor dispute, when the National Brotherhood of Operative Potters called a strike. The plant continued to operate and the strike was broken by the next Spring.

1936 saw one to the biggest changes at Shenango. Theodore Haviland came to them seeking an American company to make the famous Haviland dinnerware. They were so impressed with the quality of Shenango, an agreement with just a handshake was made with Mr. Smith. Many reasons have been given for the Haviland move to an American manufacturer – the impending war in Europe high duties on imported china and mounting costs.

From 1936 to 1958, Shenango Pottery Company made china for the Theodore Haviland Company of France using their formula, blocks cases, decals, etc. which the Havilands brought here. This ware was marketed with the trademark “Theodore Haviland New York made in America.” This china can be found everywhere. A set of Haviland manufactured in New Castle for a dinner honoring King George VI and Queen Elizabeth was sold to the New York World’s Fair in 1939. When the Fair closed this china along with pieces of Lennox china were shipped to the White House for the State Dining Room. This ware was used there during the terms of Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman.

Castleton China

Mr. Helleman sensed a need for contemporary design in shape and decoration and commissioned outstanding artists to create fresh new design. One of the most notable achievements in ceramic art was Castleton’s Museum shape designed by Eva Zeisel under the auspices of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It was hailed across Europe and America as a new epoch in ceramic history. It has been on display in many American collections and in many European Museums including the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Royal Society of Art in London.

[to learn more about the incredible career of Eva Zeisel, visit her official website: https://www.evazeisel.com/]

In 1956 Ervin Kalla, noted sculpture and ceramist redesigned place setting items in the Museum shape. The new shape in plain white with platinum trim was known as Symmetra.

In 1955, Castleton was commissioned by Mrs. Dwight D. Eisenhower to create a formal design of gold service plates for the state dining room at the White House. William Craig McBurney Director of Design at Shenango designed this. To commemorate President Eisenhower’s First birthday in the White House, another studio design was created. This decoration of intertwined doves was a Pennsylvania Dutch symbol signifying love and peace. Shenango also created the china for Eisenhower’s plane “The Columbine.”

Louise Shoaf is shown hand-applying liquid gold to the handle of a cream soup bowl for the new White House state service. After the bowl is hand-lined, it is fired in a decorating kiln.

In 1968, Shenango was commissioned by the White House of President Lyndon B. Johnson to make a new service. This was designed by the Tiffany Company of New York featuring wild flowers of the United States. Shenango ceased production of Castleton in 1974.

Dorothy Gaibis is shown applying a decal to one of 24 large bowls in the new White House state service. The service, designed by Tiffany & Co., New York, was manufactured by Castleton China of the Shenango Products Division of INTERPACE Corporation. Mrs. Gaibis, after applying the decal, removes water bubbles from under the decal to assure decoration is in complete contact with the ware.

Shenango China's Later Years

During the late 30’s, Mr. Smith became convinced that America would soon be in the war. He began building three bisque 70′ tunnel kilns and one 105′ kiln. Delayed steel shipment caused the kilns to be raised under circus tents. Wartime created many difficulties. Young skilled workers went off to war. Many employees went to work in defense industries, which paid higher wages.

Although government contracts made up over 50 percent of all production, critical materials forced substitutes. Due to this hardship, more creative methods of decorating, mixing color and packing were devised. In addition, during the war CIO-USWA won the right to represent the workers. With the end of the World War II, it became apparent that a balanced expansion would have to be achieved. The government ware made during the ware was one fire, plain white ware or with little decoration. In the post-war economy there would by a large demand for dinnerware and overglaze hotelware. A building plan was initiated in 1945 and completed in 1947. The addition contained 150,000 square feet for decoration and a 60,000 square foot building with a 200′ tunnel kiln was built for a new refractories division.

During the war, they also made the ceramic parts for land mines. A group of local businessmen including officers of Shenango formed a company for this express purpose. Later this led to a minority stockholder suit, which occupied the officers and directors for a ten-year period.

In the 1939-49 period Shenango had grown by ten times, but the company was in dire financial straits due to a number of circumstances one being the expensive expansion program had been made without long term financing. Application was made to the reconstruction finance corporation for a long-term loan. This was approved. Labor strife in the 1950’s had a drastic effect on the company’s fortunes as two strikes took place.

In 1954, the name was changed to Shenango China, Inc., bringing it back to the original 1901 name. Effort was made to mechanize. They developed the first fast fire kiln, which revolutionized the vitrified china industry. For the first time Shenango had a kiln that would fire glost ware as fast as one hour and ten minutes. Previously firing would take 36 to 40 hours. The Minority stockholders suit was finally settled in 1958. This resulted in the trustees of the Smith estate selling their controlling interest in Shenango China to Sobiloff Brothers. By 1959, all the stockholders had sold their shares to Sobiloff. The assets of Shenango China were transferred to a newly formed subsidiary of Sobiloff’s, Shenango Ceramics Inc. The working capital of the company was pledged for loans to finance other Sobiloff interests. Under the ownership of Sobiloff, Shenango purchased Wallace China on the West Coast and Mayer China in Beaver Falls, PA. These purchases added a new dimension to Shenango sales.

In 1968, Interpace Corporation bought Shenango Ceramics and her wholly owned subsidiaries. Interpace already manufactured Franciscan (earthenware) and fine china. Under the management of Interpace, the plant was expanded and modernized. A complete cup system, new bisque kilns and decorating kilns were built. They also introduced the “Valiela” decorating process, which greatly reduced the cost of print. Eleven years later, in 1979 Interpace sold the Shenango plant to Anchor Hocking Corporation of Lancaster, Ohio. Anchor Hocking continued to modernize, installing computerized body batch making, new clay forming, decorating, and firing equipment.

More changes soon were to come. In 1987, Anchor Hocking sold Shenango China to the Newell Company of Freeport, Illinois. Six months later they sold the plant to Canadian Pacific, the parent company of Syracuse China. Syracuse closed the plant and reorganized. Former employees had to reapply for their positions. Many were not hired back.

In 1989, Canadian Pacific decided to divest itself of its china manufacturers, selling Shenango, Mayer, and Syracuse to the Pfaltzgraff Company of York, PA. The Mayer operation was moved to the Shenango plant. Plans were made for further expansion, but the economic downturn and changes in demand resulted in consolidation and the eventual closing of the Shenango plant. The Shenango Indian had become an Onondaga.

Video - Preserving a Legacy (Hoyt Center for the Arts)

Run time: 03:53 min

Shenango China Exhibit: Preserving A Legacy (January 2013)

Presenters: Robert Presnar, Education Director and Kim Koller-Jones, Executive Director, Hoyt Center for the Arts

“The Pottery” has not only contributed to our local and international fame, the Shenango Indian, a symbol of the original American potters, is also a constant reminder of the plant’s service, dependability, quality, and ever present commitment and talent of its workers – a lasting legacy of pride and beauty.